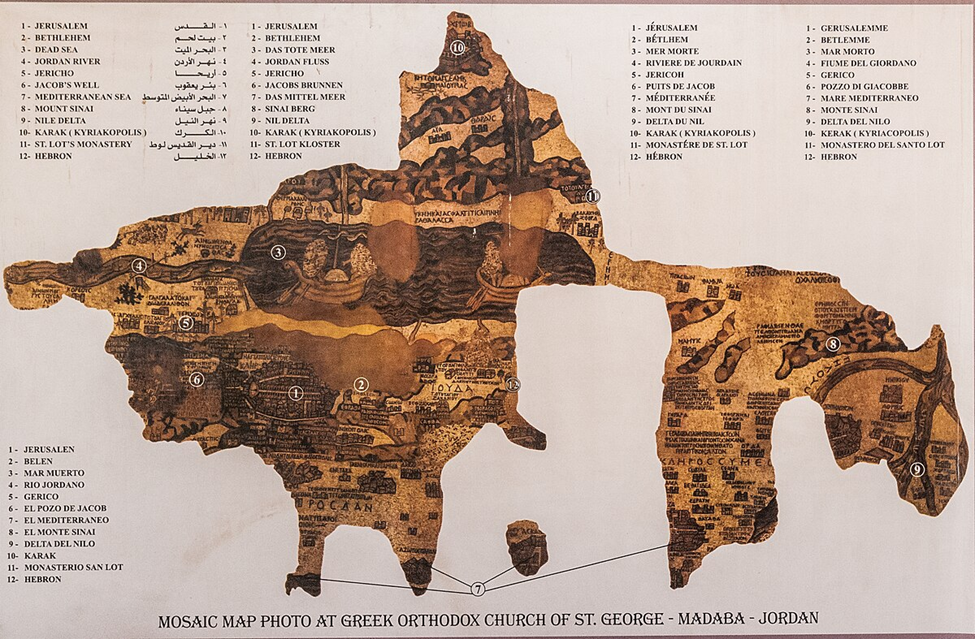

Anovia- The Madaba Mosaic Map, also called Madaba’s Holy Land Map, stands as one of the most remarkable archaeological treasures of the Byzantine world. It is the oldest surviving mosaic map of the Holy Land, crafted in the second half of the 6th century CE.

Accidentally discovered around 1890, when residents of the newly resettled village of Madaba began constructing the Church of St. George atop the ruins of a Byzantine structure, the map today survives across an impressive 10.5 × 5 meters, although originally it may have reached nearly 21 × 7 meters in size.

Oriented eastward in alignment with the church altar, its visual span extends from Lebanon in the north to Egypt’s Nile Delta in the south, bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the west and the Eastern Desert to the east.

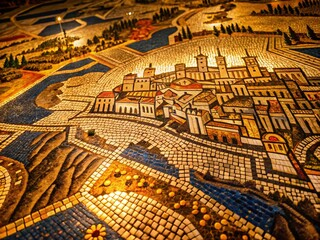

Composed of more than two million colored stone tesserae, the mosaic offers an unparalleled geographical and cultural portrait of the region. Its rich palette—blues, reds, yellows, greens, and purples—brings to life landscapes, cities, flora, fauna, and waterways, from the winding Jordan River to the palm-lined oasis of Jericho.

The map’s exceptional level of detail includes over 150 Greek inscriptions naming towns, villages, biblical references, and quotations from ancient texts such as the Onomasticon of Eusebius and the works of Flavius Josephus.

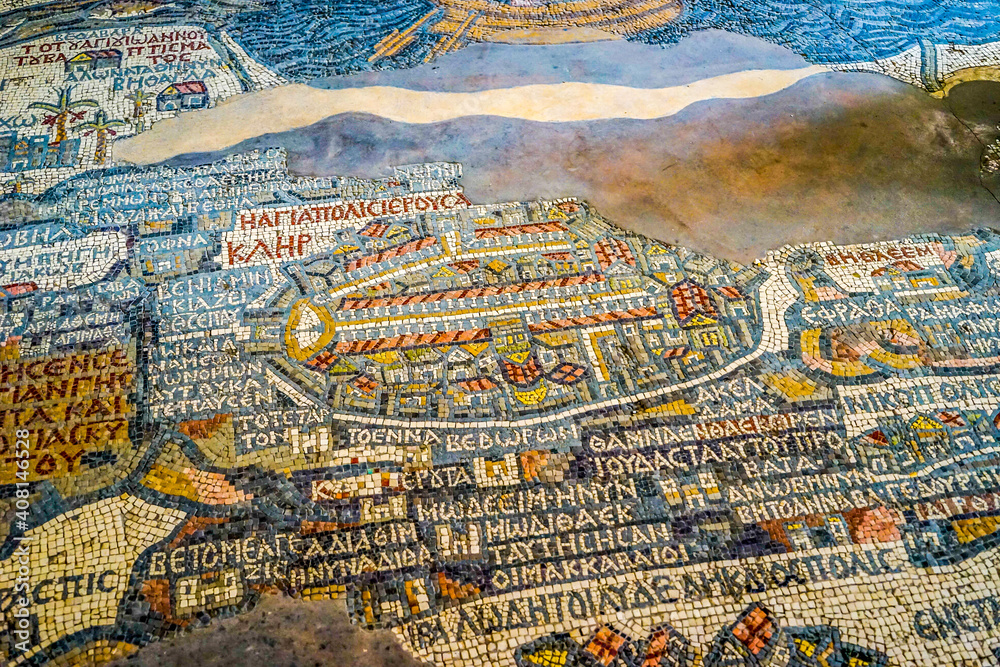

The depiction of Jerusalem, lies in its center is considered its most celebrated feature. Presented on a scale larger than any other city on the mosaic, Byzantine Jerusalem appears with extraordinary architectural clarity, 19 towers, six city gates, three main streets, 11 churches, and numerous public buildings.

Significantly, the map preserves the only known artistic representation of the original Church of the Holy Sepulchre as constructed under Emperor Constantine in the early fourth century.

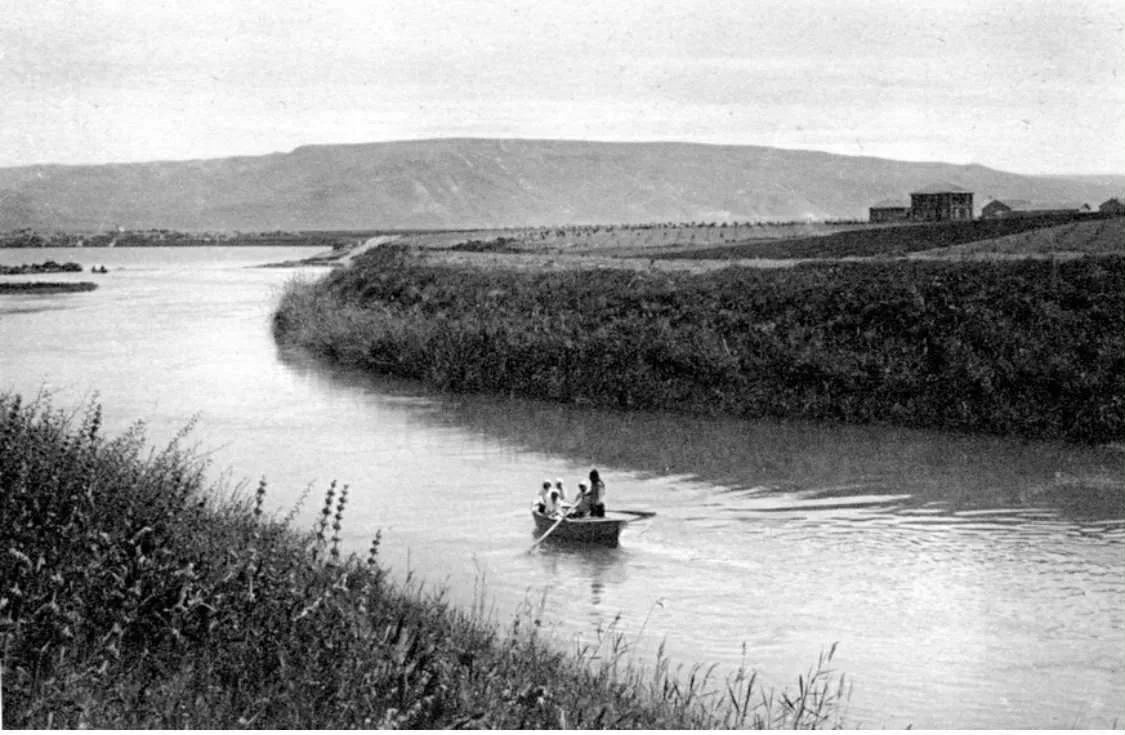

Other cities, including Ashkelon and Gaza, are rendered with similar care, while scenes such as fish swimming in the Jordan River or a lion hunting a gazelle in the Moab region showcase the artisans’ creativity.

Beyond geography, the Madaba Mosaic Map of Saint George offers insights into 6th-century economic and social life, illustrating date and balsam cultivation around Jericho, the movement of transport ships across the Dead Sea, and the network of overland pilgrimage routes connecting major biblical sites, reflecting the flourishing pilgrimage economy of the period.

What is certain is that the Madaba Mosaic Map is far more than a visual record; it is a cultural, artistic, and historical masterpiece. For historians, pilgrims, and travelers alike, standing before it is akin to opening a living history book—one in which every tile contributes to the story of a land central to faith, identity, and human civilization.

The Origins of Madaba’s Holy Land Map

The surviving portion of the Madaba Mosaic Map today measures roughly 35 by 15 feet, about 560 square feet, yet scholars widely agree that this represents only a fraction of its original grandeur.

Most estimates place the full mosaic at around 1,000 square feet, while some researchers argue it may once have been nearly twice that size. Even using the more conservative figures, the original composition would have contained more than one million tesserae, each meticulously set into place by Byzantine artisans.

Reconstructing the complete extent of the map remains a subject of scholarly debate. Conservative reconstructions place its northern boundary along the Phoenician coast and its southern limit as far as Mount Sinai and the ancient Egyptian city of Thebes, broadly mirroring the borders of the Promised Land described in Numbers 34:1–12.

Other scholars propose a far more expansive vision, suggesting the mosaic may once have depicted Asia Minor, Crete, Cyprus, the Red Sea, and even stretches of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers.

These differing interpretations underscore the map’s extraordinary scale and the ambitious geographical knowledge behind its creation.

Among the distinguished figures who have visited the mosaic is Pope John Paul II, the only pope to have viewed it in person. During his historic Millennium pilgrimage to the Holy Land in March 2000, he traveled to Madaba and visited the Church of St. George specifically to see the renowned mosaic map. His pilgrimage through Jordan also included other prominent Christian sites, such as Mount Nebo—further highlighting Madaba’s enduring spiritual significance.

Palestine and Jerusalem

At the heart of the Madaba Mosaic Map lies its most elaborate and detailed element: Jerusalem.

Positioned at the center of the composition, the Byzantine city appears as a meticulously rendered urban plan, showcasing many of its most significant monuments.

Clearly visible are the Damascus Gate, Lions’ Gate, Golden Gate, and Zion Gate, alongside architectural landmarks such as the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the New Church of the Theotokos, the Tower of David, and the city’s main north–south street, the Cardo Maximus.

The mosaic even marks Acel Dama, the “field of blood” known from Christian liturgy, on the southwestern side of the city.

This exceptional level of detail makes Jerusalem the visual and symbolic centerpiece of the map, underscoring its primacy in Byzantine religious geography.

Gaza and its surrounding

Gaza appears on the map as a significant Byzantine bishopric and thriving urban center. Although only the southern half of its vignette survives, the mosaicist clearly sought to emphasize the city’s architectural splendor.

Like Jerusalem, Gaza is represented as a walled oval, anchored by a colonnaded Cardo running east–west, corresponding closely to modern as-Suq al-Kabīr street. At the intersection of the Cardo and Decumanus lies a spacious central square, believed to align with today’s Khān az-Zēt area.

In the city’s southwest, the mosaic originally included two prominent churches. Sixth-century rhetorician Chorikios of Gaza described in detail the Church of St. Sergius and the Church of St. Stephen, both famous in his hometown. However, because the mosaic is incomplete, identifying the two preserved church structures with absolute certainty remains impossible.

In the southeastern quadrant of Gaza, a theater stands out clearly. Archaeologist Zeev Weiss attributes its construction to the Roman imperial period and suggests that it was later incorporated into the city’s defensive walls. The yellow semicircle at the center is interpreted as the orchestra, while the surrounding white and pale-red arcs represent the divided cavea. The dark red stripes separating the outer cavea into segments likely depict stairways (scalariae).

To the northwest of Gaza, the mosaicist depicted the city’s port, identified by the partially preserved inscription “Maioumas, also Neapolis. To the southwest, a Church of Saint Victor appears with a distinctive red-roofed portico.

The Pilgrim of Piacenza recorded the tomb of Saint Victor as located within Maioumas itself, rather than between Maioumas and Gaza as shown on the mosaic—an intriguing discrepancy for scholars.

Further south of Gaza, the map records a cluster of villages, some of which are attested only through the Madaba Map, suggesting that the mosaicist possessed direct, local knowledge of these communities. This unique topographical precision highlights the map’s value not only as an artistic masterpiece but also as a geographical document shaped by firsthand familiarity with the land it portrays.

Jericho and the Jordan Valley

One of the best-preserved sections of the Madaba Mosaic Map portrays the lower Jordan Valley and the flourishing oasis of Jericho, surrounded by several early Christian pilgrimage sites. The landscape is animated with depictions of wildlife and vegetation: on the eastern bank, a Nubian ibex flees from a large predator, likely a leopard, whose features were later defaced by iconoclasts. In the Jordan River, fish swim upstream, with one distinctive fish turning back to avoid entering the Dead Sea, whose high salinity makes it uninhabitable for aquatic life.

Around Jericho and in scattered areas across the region, the mosaicist depicted numerous date palmsand shrubs whose egg-shaped leaflets are tentatively identified as balsam (Commiphora gileadensis). Since antiquity, the cultivation of dates and balsam formed the economic backbone of the Jericho area.

Unfortunately, balsam production declined in the early Islamic period with the broader collapse of plantation agriculture.

Jericho itself is rendered not through a detailed vignette but as a stylized, medium-sized city marked by walls, five towers, and two gates. Three church roofs appear within the city, though they cannot be conclusively matched to known ecclesiastical structures.

Neapolis (Nablus) and Its Surroundings

Between Jerusalem and Neapolis, the mosaic includes a striking text panel in red letters on a brown background, combining two biblical blessings bestowed on the tribe of Joseph, quoted from the Septuagint:

- Genesis 49:25: “Joseph, God has blessed you with the blessing of the earth, with the choicest gifts of the ancient mountains.”

- Deuteronomy 33:13: “And of Joseph he said: Blessed of the Lord is his land, with the precious things of heaven.”

Neapolis appears as a large city vignette, though damaged and blackened by fire. A preserved portion of the city wall reveals several towers. From the East Gate, a colonnaded street runs westward to the West Gate, crossing the north–south axis of the city. Near this intersection stands a small columned structure, possibly a thermal bath, located approximately where the an-Naṣr Mosque stands today.

At the southern edge of the city, a conspicuous semicircular form may represent a nymphaeum, an interpretation supported by modern excavations at ʿAin Qaryun. A large basilica visible on the map may correspond to the city’s principal church, known to have been damaged in 484 during a Samaritan attack.

Before the Gates of Jerusalem

Above the Jerusalem vignette, the map shows Gethsemane as a small church. To the left, a corrected Septuagint version of Deuteronomy 33:12 appears with the blessing over the tribe of Benjamin:

“Benjamin, God protects him, and he dwells between his mountains.”

The correction reflects an attempt to restore the Hebrew meaning of “shoulders” as a poetic reference to mountain slopes.

Several roads are indicated around Jerusalem. The only overland road marked with white tesserae is the route from the Damascus Gate to Neapolis (Nablus). Another road is identified through its milestones: west of Jerusalem, the map labels the “fourth milestone” and the “ninth milestone” on the route toward Nikopolis and Diospolis (Lydda).

Further south lies Bethoron, with the “Ascent of Bethoron,” a location mentioned multiple times in the Bible and perhaps symbolized by the dark tesserae beneath the name.

East of Bethoron appears Modeïm now Moditha, the ancestral home of the Maccabees, described here almost verbatim from Eusebius of Caesarea’s Onomasticon.

The road continues to Thamna “where Judah sheared his sheep” (Genesis 38:12–13), and to Akeldama, the “field of blood” associated with Judas Iscariot (Matthew 27:6–8), located near Mount Zion according to Eusebius.

Refrences:

Frithowulf, Hrothsige. “Madaba Map: An Antique to Early Byzantine Floor Mosaic

Herbert Donner – The Mosaic Map of Madaba: An Introductory Guide

Madaba: The World’s Oldest Holy Land Map.” Biblical Archaeology Review (BiblicalArchaeology.org),