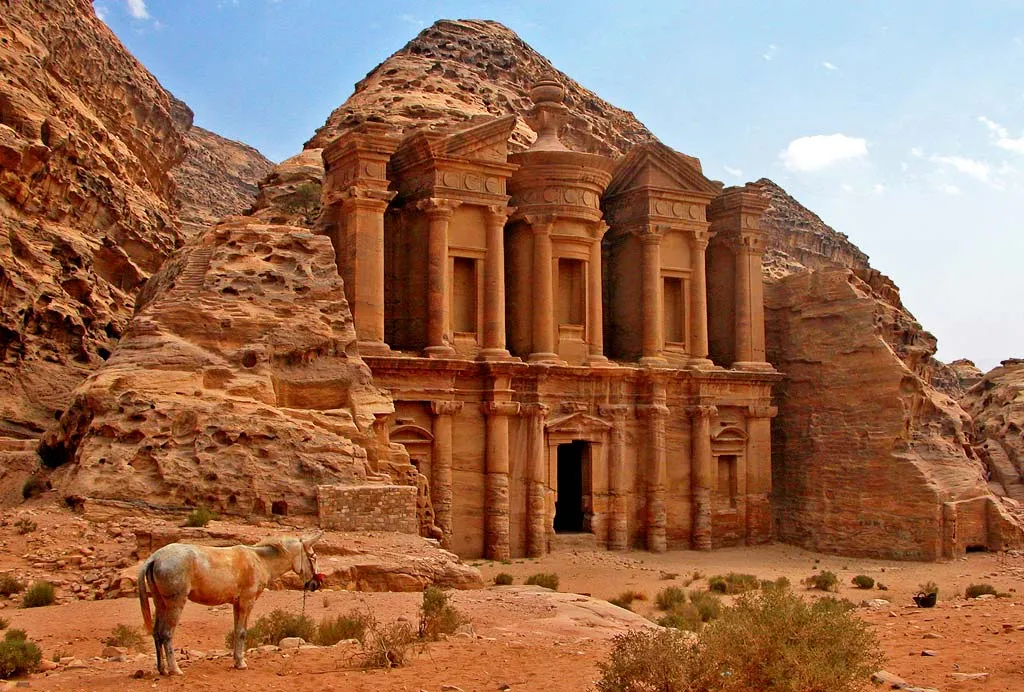

Anovia Exclusive- In the winter of 1993, Petra revealed a secret it had been guarding for more than fourteen centuries. Beneath the charred remnants of a Byzantine church in Petra, archaeologists uncovered a treasure unlike any other in Jordan’s history: nearly 140 carbonized papyrus scrolls.

Inside a small room on the northeast side of its Byzantine church in Petra, archaeologists stumbled upon a cache of nearly 140 papyrus scrolls, blackened, fragile, and astonishingly intact.

The blaze that swept through the church around 600 CE had destroyed mosaics and weakened the structure, yet it had an ironic consequence: it carbonized the papyri, preserving them rather than erasing them from history, as Barbara Porter of the American Center of Oriental Research (ACOR) explained during our first interview in 2013, published in the Jordan Times daily.

“The scrolls survived the fire that took place in 600 AD and caused the papyri to carbonise, and, ironically, be preserved.” In Petra’s harsh desert environment, where organic materials rarely endure, the survival of these documents is nothing short of miraculous.

Today, this trove is known as the Petra Papyri, the largest archive of ancient texts ever uncovered in Jordan, and one of the most significant finds outside Egypt. Written mostly in Greek, yet sprinkled with Nabataean and early Arabic names, the scrolls once belonged to Theodoros, son of Obodianos, a church deacon who rose to become archdeacon. His family archive offers a vivid portrait of everyday life in Byzantine Petra: real-estate transactions, dowries, inheritance disputes, loans, contracts.

Beyond the human stories, the texts also chart Petra’s place within the Byzantine world. They reveal how Emperor Justinian’s laws, issued in Constantinople, were applied in Petra almost immediately, underscoring the city’s legal and cultural ties to the empire.

Because of their delicate state, the scrolls could not be taken abroad. Instead, Finnish papyrologists led by Jaakko Frösén conserved them in American Centre of Research ACOR at the capital of Jordan, between 1994 and 1995, mounting each fragment between rice paper and glass. Many have since been published in the Petra Papyri series, and select pieces are now on display at the ACOR, allowing visitors to connect directly with Petra’s Byzantine past.

The church itself, discovered in 1990 by archaeologist Kenneth Russell, is a full-fledged cathedral, built around 450 CE on layers of Nabataean and Roman remains. Its mosaic floors, spanning 70 square meters, depict the seasons, the earth, the ocean, and wisdom, artworks as eloquent as the scrolls themselves. Today, a protective shelter allows visitors to wander the ancient aisles and witness this rare fusion of art, faith, and history firsthand.

Together, the church and its papyri form a dialogue across time: a record of faith, law, and daily life in a city at the crossroads of empires and cultures. For travelers to Petra today, the scrolls and the church are not just historical artifacts, they are an invitation to walk through centuries, to see how stories, laws, and lives once intertwined in this desert jewel.